What is fascia and how can work on fascia help to relieve chronic pain, tension, stiffness and imbalances in our bodies?

Fascia is one of the most important and interconnected systems within the body. Until quite recently is was very much ignored within mainstream anatomical and medical thinking. Interest and research into fascia has increased a huge amount in the last 10 years, to the extent that many new ideas are changing the way we think about the body. You could say that fascia is not new but our understanding of it is!

A good nerdy definition can be taken from the International Fascial Research Congress (a wonderful organisation set up by pioneers in the field of fascial research):

Fascia is the soft tissue component of the connective tissue system that permeates the human body. It forms a whole body continuous three-dimensional matrix of structural support. Fascia interpenetrates and surrounds all organs, muscles, bones and nerve fibres, creating a unique environment for body systems functioning.

International Fascial Research Congress

If you read that and found it difficult to understand you are not alone! The key phrase is that fascia is “the soft tissue component of the connective tissue system“. It forms ligaments, tendons and wraps around the brain, nerves, bones muscle fibers and bundles of muscle fibers. These fasciae were previously labelled as different structures (e.g. epimysium, perimysium, endomysium), yet the mind-boggling truth is that these things are one fascia and all interconnected through a silk-like spider’s web. Imagine for one moment if your entire body was to be dissolved leaving only the fascia behind……you would in fact still have a complete 3D representation of you.

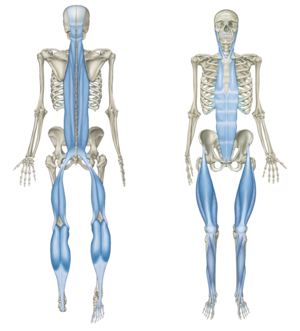

Our new understanding of fascia is challenging many long held beliefs about how the body works. For example, Tom Meyers has developed the idea of ‘myofasical trains, chains and slings’ in his work. He suggests that our previously held belief that ‘muscles just operate over a single joint’ are too simplistic – instead because muscles are connected in various ways to fascia that cross several joints and can span from head to toe, we are therefore in effect dealing with a series of much larger ‘cardinal slings’ that cover the entire body. This means that pain or dysfunction experienced in one part of the body, may have its origins in a different, apparently unrelated part of the body.

Fascial restrictions do not show up on CAT scans, MRI’s or x-rays, and many people suffer with unresolved physical or emotional pain due to blockages or trauma in their fascia. Fascial tension is common and most of us will have restricted fascial tissue somewhere in our bodies. For it to function properly fascia likes to move, something which is an issue in a society of desk-based jobs, excessive driving and sitting. It also likes to be hydrated, so that means drinking plenty of water which many of us do not do. When fascia is not hydrated, it loses its ability to glide freely and becomes stuck. Fascia can also become stuck through trauma such as whiplash, and is further affected by operations where tissues are cut leaving scar tissue behind.

There are a number of different forms of fascial work commonly practiced in the UK, some therapists are trained in multiple forms and will often blend these together in a treatment session:

Myofascial Release: developed by Robert Ward and John F. Barnes, myofascial release is generally passive, with the client staying relaxed. Gentle but sustained pressure is applied to fascia to allow the tissues to elongate. Areas of fascial tension may need to be held for several minutes. Sometimes the ‘release’ is felt by both the client and the therapist, and has been described as anything from ‘melting, like a wave’ through to ‘a sense of teasing matted, almost felted wool to loosen and create space within (my) tissues’.

Rolfing or Structural Integration: Developed by Ida Rolf in the late 1940’s when she was investigating the human body in relation to gravity. Rolfing seeks to change the alignment of the whole of the body, easing pain and dysfunction caused by fascial restrictions. Practitioners will work with clients over 10 sessions through the whole of the body from feet to head. The work is active involving movement by the client. Other similar approaches include Kinesis Myofascial Integration as developed by Tom Myers, and Hellerwork (both are based heavily on Rolf’s work and retain many of her original ideas and concepts).

Craniosacrial Therapy: developed by John F. Upledger in the 1970’s as an offshoot of osteopathy. Using a soft touch generally no greater than 5 grams, practitioners release restrictions in the craniosacral system (literally the head and sacrum) to improve the functioning of the central nervous system. The head, sacrum (tail-bone), feet and trunk may all be worked with during a session.

It is worth remembering that it is impossible to touch the body without touching the fascia, and therefore, it makes sense to integrate a variety of fascial techniques into any bodywork session. Doing fascial work requires a willingness to follow intuition, a deep sense of connection to the body and the development of a ‘listening touch’. Whether direct techniques (Structural Integration or Rolfing), indirect techniques (myofascial release or cranial sacral work) or a combination of both are used, the results can be very powerful. Conditions such as whiplash, sciatica, carpal tunnel syndrome, RSI, sporting injuries, rotator cuff issues, fibromyalgia, pelvic and menstrual problems, IBS and headaches can all be treated successfully.

References

Chaitow, L. (2014) Somatic dysfunction and fascia’s gliding potential. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 18 (1), 1-3

Duncan, R. (2016) Myofascial Release. Human Kinetics: USA.

Fairweather, R. and Mari, M. S. (2016) Massage Fusion: the Jing method for the treatment of chronic pain. Handspring Publishing, Edinburgh.

Karrasch, N. (2012) Freeing Emotions and Energy through Myofascial Release. Singing Dragons: London.

Myers, T. W. (2001) Anatomy Trains, 1st Edition. Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh

Myers, T. W. and Earles, J. (2017) Fascial Release for Structural Balance, Revised Edition. Lotus Publishing: Chichester.